Colorectal Polyp Types: Understanding Adenomas vs. Serrated Lesions

Nov, 16 2025

Nov, 16 2025

When you hear the word polyp, it’s easy to panic. But here’s the truth: most colorectal polyps aren’t cancer. They’re like warning signs-abnormal growths that, if left alone, might turn into cancer over time. The key isn’t fear. It’s knowing the difference between the types, how they behave, and what to do next.

Two Main Paths to Colon Cancer

Not all polyps are created equal. About 70% of precancerous polyps are adenomas. The other 20-30% are serrated lesions. These two types follow completely different paths to cancer, which is why doctors now treat them differently.

Adenomas grow slowly, often over 10-15 years. They start as small bumps on the colon lining and, if they get bigger or change shape, they can turn malignant. Serrated lesions, on the other hand, are sneakier. They’re flatter, harder to spot, and can turn cancerous faster-sometimes in just 5 years. That’s why missing one during a colonoscopy can be dangerous.

Adenomas: The Classic Precancer

Adenomas come in three main shapes, and each tells you something about cancer risk.

- Tubular adenomas make up about 70% of all adenomas. They’re small, round, and grow like tiny tubes. Most are harmless if caught early. If one is under half an inch (1.27 cm), the chance of cancer is less than 1%.

- Tubulovillous adenomas are mixed-part tube, part finger-like projections. They’re less common, about 15% of adenomas, and carry a higher risk. The more villous tissue they have, the more likely they are to hide cancer cells.

- Villous adenomas are the rarest, only 15% of cases, but the most dangerous. They’re flat, spread out, and often too big to remove easily. If one is over 1 cm, there’s a 10-15% chance it already contains cancer. Their shape makes them harder to remove completely during colonoscopy, which is why follow-up is critical.

Size matters. A polyp under 0.5 cm? Low risk. One over 1 cm? Time to take action. And if it has villous features? Even more reason to be thorough. That’s why doctors measure every polyp and check its structure under the microscope.

Serrated Lesions: The Silent Threat

Serrated lesions are named for their jagged, saw-tooth look under the microscope. There are three types, but only two are truly dangerous.

- Hyperplastic polyps are common, especially in the lower colon. Most are harmless. If they’re small and in the rectum, they rarely turn cancerous. You can often ignore them after removal.

- Sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) are the real concern. They’re flat, often hidden in the upper colon (cecum or ascending colon), and easy to miss during colonoscopy. Up to 68% are found in the proximal colon. Their shape and location mean they’re missed in 2-6% of standard screenings. When they do turn cancerous, they follow a different genetic path-often with BRAF mutations and DNA methylation-making them harder to predict.

- Traditional serrated adenomas (TSAs) are rare but aggressive. They’re usually in the left colon and grow faster than adenomas. They’re more likely to show high-grade dysplasia, meaning the cells are already changing in dangerous ways.

Here’s the scary part: a 2016 study found that SSA/Ps had a cancer risk nearly equal to conventional adenomas-13% vs. 12.3%. That means a small, flat, seemingly harmless polyp in your right colon could be just as risky as a large, bulbous adenoma.

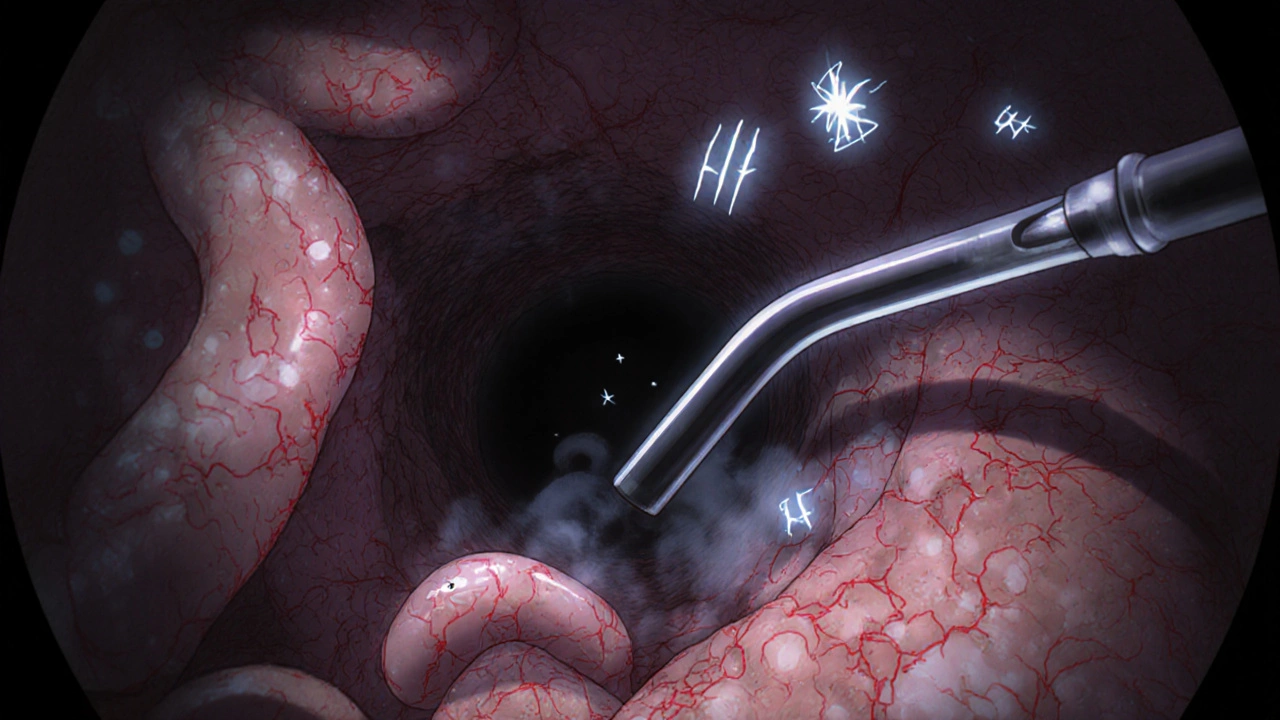

Detection: Why Some Polyps Escape Notice

Not all polyps are easy to find. Pedunculated polyps-those with a stalk-stick out like mushrooms. Easy to spot and remove.

Sessile and flat polyps? They’re the troublemakers. They lie flat against the colon wall. During a colonoscopy, they blend in with the normal tissue. Even the best doctors can miss them.

That’s why newer tools matter. AI-assisted colonoscopy systems like GI Genius have been shown in trials to boost adenoma detection by 14-18%. That’s not just a number-it’s lives saved. These systems highlight subtle color changes, surface irregularities, and crypt patterns that human eyes might overlook.

SSA/Ps are especially tricky. Under magnifying colonoscopy, they show round, open pit patterns and twisted blood vessels. Without this tech, they’re invisible. That’s why some experts now recommend high-definition colonoscopies with chromoendoscopy for high-risk patients.

What Happens After Removal?

Getting a polyp removed doesn’t mean you’re off the hook. It means you’ve started the next phase: surveillance.

For a small tubular adenoma (<1 cm), most guidelines say a repeat colonoscopy in 7-10 years. Simple.

But if you had an SSA/P that’s 10 mm or larger? That’s where things get complicated. The U.S. recommends a follow-up in 3 years. Some European guidelines say 5. Why the difference? Because studies in Europe show slower progression. But in the U.S., where SSA/Ps are more commonly found with advanced changes, 3 years is the safer bet.

And if you had a villous adenoma or a TSA? You’ll likely need another colonoscopy in 3 years, no matter the size. These are high-risk polyps. One mistake, one missed follow-up, and the window for prevention closes.

Complete removal is everything. For adenomas under 2 cm, success rates are 95-98%. For large SSA/Ps? Only 80-85%. That’s why some need to be removed in pieces, or even require surgery if they’re too big or too flat. A polyp that’s not fully removed is a ticking clock.

Who’s at Risk? And What Should You Do?

Most people with polyps never get cancer. That’s true. But your risk goes up if:

- You’re over 50

- You have a family history of colorectal cancer or polyps

- You’ve had a serrated polyp before

- You smoke, drink heavily, or have obesity

- You have type 2 diabetes

And here’s something new: colorectal cancer is rising in people under 50. We don’t fully know why, but it’s real. That’s why the American Cancer Society now recommends starting screening at 45-not 50.

If you’ve had any polyp, your risk of future cancer is 1.5 to 2.5 times higher than someone who hasn’t. That doesn’t mean you’ll get it. It means you need to stay on schedule with screenings.

The Future: Personalized Surveillance

Right now, we use polyp size and type to decide when to schedule your next colonoscopy. But that’s changing.

Researchers are now looking at the molecular fingerprints of polyps. Adenomas often have APC gene mutations. Serrated lesions? BRAF mutations and CIMP (CpG island methylator phenotype). Soon, we won’t just say, “You had a large SSA/P-come back in 3 years.” We’ll say, “Your polyp has high-risk methylation markers-come back in 18 months.”

Within five years, molecular testing of polyps will likely be standard. That could cut the 6.5 million surveillance colonoscopies done each year in the U.S. by 20-30%. Fewer procedures. Fewer risks. Better outcomes.

For now, the message is simple: get screened. Get polyps removed. Follow up. Don’t ignore a flat spot on your colon lining. It might look harmless. But in the right conditions, it could be the start of something serious.

Julie Roe

November 17, 2025 AT 14:25Really glad someone broke this down without the fear-mongering. I had no idea serrated lesions could be just as dangerous as adenomas, especially the SSA/Ps. My doc never explained why my last colonoscopy took so long-they were scanning the right side like it was a treasure hunt. Turns out they were looking for flat, sneaky stuff. Feels good to know it’s not just about size anymore.

Also, the part about AI tools like GI Genius? Huge. My cousin missed a polyp last year because it was hidden in a fold. If tech can catch what human eyes miss, we should be pushing for it everywhere, not just fancy clinics.

Ashley Unknown

November 19, 2025 AT 02:08Okay but let’s be real-colonoscopies are a scam. I read a guy on Reddit who said 40% of polyps are removed just to make doctors look busy. And AI? More like surveillance tech disguised as medicine. They’re not saving lives-they’re selling follow-ups. You think they care if you live or die? They care about your insurance billing code.

My aunt had three polyps removed last year. Two were hyperplastic. Guess what? She got a 3-year follow-up. That’s not medicine. That’s profit-driven panic.

Margo Utomo

November 19, 2025 AT 16:29Yessssss this is the info I needed 😭👏

SSA/Ps are the silent assassins of the colon. I used to think if it didn’t look like a mushroom, it wasn’t a problem. Nope. Flat and sneaky = way scarier.

Also AI colonoscopy? YES PLEASE. My gastro said they upgraded last month and now they catch 2x more. I cried. Not because I’m dramatic-because I finally feel like someone’s actually trying to save me, not just check a box. 🤍🩺

Christina Abellar

November 20, 2025 AT 14:21Thanks for this. Clear, useful, and not overwhelming.

Eva Vega

November 22, 2025 AT 01:02The histopathological classification of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps (SSA/Ps) warrants particular attention due to their distinct molecular pathway involving BRAF mutations and CpG island methylator phenotype (CIMP), which differentiates them from conventional adenoma-carcinoma sequences. This has direct implications for surveillance intervals and screening modality selection in high-risk cohorts.

Joyce Genon

November 23, 2025 AT 06:19Ugh. I read all this and I’m still not sure what I’m supposed to do. Adenomas? Serrated? Villous? Tubulovillous? Who even uses these words outside of a textbook? And now they want me to get a colonoscopy every 3 years? What if I don’t have insurance? What if I’m scared? What if I just want to eat my damn bacon and not think about my colon?

And don’t even get me started on AI. Yeah, great, another gadget that costs $20,000 and only works in Boston hospitals. Meanwhile, my rural clinic still uses a 2010 camera and the doc says ‘looks fine’ and we’re done. So yeah, thanks for the science lecture but I’m still just trying to survive the next 10 years without getting a colostomy bag.

Also, why is everyone acting like this is new info? My grandma had a villous adenoma in 1998 and they told her the same thing. Nothing’s changed except the buzzwords. And now we’re supposed to be impressed by AI? I saw a TikTok that said a robot can now diagnose your poop. I’m not even kidding. That’s the future? I’m out.

Dave Feland

November 24, 2025 AT 09:12Let me guess-this post was sponsored by GI Genius. The 14-18% detection increase? Published in a journal owned by Medtronic. The real cancer risk from SSA/Ps? Inflated by the same researchers who patent the endoscopic tools. The entire screening-industrial complex is a Rube Goldberg machine designed to extract revenue from asymptomatic populations. You think your polyp was ‘missed’? It was never meant to be found. It was meant to be monetized.

And why do you assume all doctors are altruistic? The average gastroenterologist performs 400 colonoscopies per year. That’s one every 15 minutes. They don’t have time to spot flat lesions-they’re optimizing throughput. AI doesn’t fix that. It just adds another billing code.

George Gaitara

November 25, 2025 AT 23:25Okay so here’s the thing-what if the real problem isn’t the polyps? What if it’s the colonoscopy prep? I did the whole laxative thing last year. Felt like I was being poisoned by a pharmacy. And then the doc says ‘oh we missed one’-but I literally screamed for 6 hours straight in a bathroom. Was it worth it? Maybe. But I’m not doing it again unless they invent a pill that makes me dream about rainbows instead of diarrhea.

Also, why do they always say ‘it’s just a polyp’ like that’s supposed to comfort me? It’s a GROWTH. IN MY INSIDES. That’s not ‘just’ anything. That’s a tiny alien that crawled in and started building a house. I want my money back.

Georgia Green

November 27, 2025 AT 17:00Just want to add-SSA/Ps are way more common than people think, especially in women over 50. I had one found during my screening and my doc didn’t even mention it until I asked twice. I had to look it up myself. If you’re getting screened, ask if they looked at the right side with high-def. And if they say ‘we always do,’ ask how they define ‘high-def.’ Most places don’t. Just sayin’.

jalyssa chea

November 28, 2025 AT 20:22so i had a polyp removed last year and they said its hyperplastic and i was like yay but then i read this and now im scared again like what if they missed something what if its not hyperplastic what if its one of those sneaky ones and they just said it was to make me feel better like why do they even do this to us

Roberta Colombin

November 30, 2025 AT 18:23Thank you for sharing this with such care. Many people hear 'polyp' and shut down. But you’ve given us a map instead of a warning sign. I’ve shared this with my mother, who’s nervous about her upcoming colonoscopy. She said it made her feel less alone. That’s the kind of information that changes lives-not just medical outcomes, but emotional ones too.

And to those who are angry or scared-your feelings are valid. But this isn’t about fear. It’s about power. Knowing what’s happening in your body gives you power to act, to ask questions, to choose. You’re not just a patient. You’re a person with a voice.

Keep speaking up. Keep asking. We’re here with you.

Matt Wells

December 1, 2025 AT 16:14It is noteworthy that the adenoma-carcinoma sequence, as originally postulated by Vogelstein and colleagues in 1988, remains the canonical model for colorectal carcinogenesis. However, the serrated pathway, elucidated in the early 2000s, represents a paradigmatic shift requiring reclassification of surveillance protocols. The temporal dynamics of SSA/P progression, particularly in the context of CIMP-high and BRAF-mutant phenotypes, necessitate revised endoscopic follow-up intervals that are not yet universally standardized. This remains a critical gap in clinical guidelines.