Multiple Manufacturers: NTI Drugs and Switching Between Generics

Dec, 15 2025

Dec, 15 2025

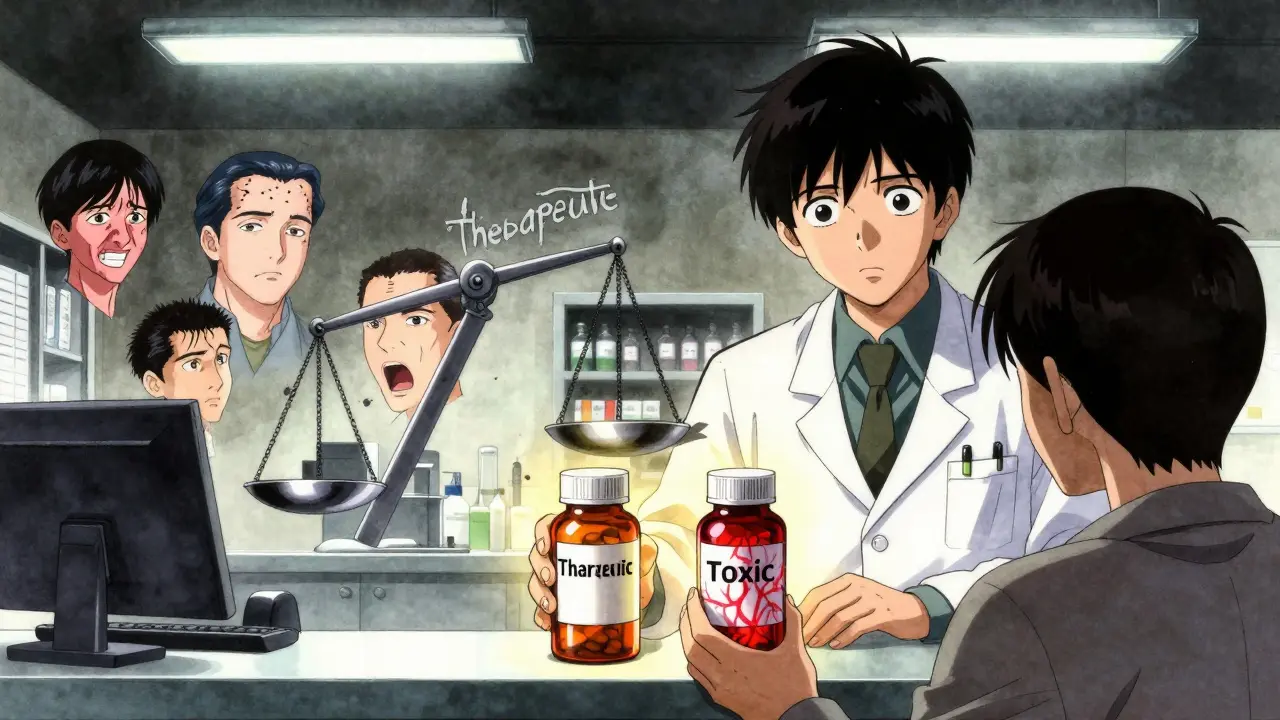

When you take a medication like levothyroxine or warfarin, even a tiny change in dose can mean the difference between feeling fine and ending up in the hospital. These are narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs - medicines where the line between working and causing harm is razor-thin. The FDA doesn’t list every NTI drug, but it’s clear on this: if you’re on one, switching between generic versions from different manufacturers isn’t as simple as swapping one brand of painkiller for another.

What Makes a Drug an NTI Drug?

An NTI drug has a very small window between the dose that works and the dose that’s dangerous. Think of it like walking a tightrope. A little too much, and you risk toxicity. A little too little, and the treatment fails. For example, digoxin - used for heart failure - has a therapeutic index of about 2. That means the toxic dose is only twice the effective dose. With lithium, used for bipolar disorder, the difference between a therapeutic level and a toxic one is barely more than a teaspoon in a bathtub.

The FDA requires stricter testing for these drugs. While regular generics must be within 80-125% of the brand-name drug’s absorption (called bioequivalence), NTI drugs must hit a tighter range: often 90-111% or even 95-105% for potency. That’s because even a 10% variation in blood levels can throw off treatment. For drugs like carbamazepine or phenytoin, that could mean uncontrolled seizures. For tacrolimus, used after organ transplants, it could trigger rejection.

Generic Switching: What Happens in Real Life?

Pharmacists are trained to substitute generics for brand-name drugs - it’s standard practice. But when it comes to NTI drugs, things get messy. A 2019 national survey found that 63% of pharmacists had received complaints from patients or doctors after switching between generic versions of NTI drugs. Patients reported fatigue, mood swings, tremors, or even seizures after switching from one generic manufacturer to another.

One study tracked kidney transplant patients who switched from one brand of cyclosporine to another. The rate of acute rejection jumped by 15.3%. Another study on tacrolimus showed that different generic versions had active ingredient levels ranging from 86% to 120% of the brand. While the average stayed within FDA limits, the variation between batches was wide enough to worry clinicians. One patient might do fine switching from Accord to Mylan, but another could have a spike in blood levels that leads to kidney damage.

Even levothyroxine, which has been studied more than any other NTI drug, isn’t risk-free. A 2021 FDA analysis of over 10,000 patients showed that switching between brand and generic levothyroxine didn’t significantly change TSH levels. But the same study noted that some patients had spikes or drops in TSH after switching - even if the average looked fine. That’s the problem with NTI drugs: population averages don’t tell you what happens to you.

Why Do Differences Even Exist?

Generic drugs must contain the same active ingredient as the brand. But they don’t have to use the same inactive ingredients - the fillers, dyes, binders, and coatings. These might seem harmless, but for NTI drugs, they can change how quickly the medicine is absorbed. A tablet that dissolves a few seconds faster can cause a spike in blood levels. A capsule with a different coating might delay absorption, leading to underdosing.

Manufacturers also tweak formulations to improve stability or reduce cost. That’s true for brand-name drugs too - but when a brand changes its formula, patients usually notice. When a generic changes, it often happens without warning. You might get the same pill, same name, same color - but it’s from a different factory, with a different recipe.

What Do Doctors and Pharmacists Really Think?

There’s a big gap between what the FDA says and what clinicians see. The FDA’s official stance is clear: approved generics are therapeutically equivalent. But a 2022 review in the Journal of Clinical Pharmacology found that 78% of neurologists still avoid automatic substitution of generic antiepileptics. The American Academy of Neurology explicitly recommends against switching patients on phenytoin or carbamazepine unless absolutely necessary.

Pharmacists are caught in the middle. In 27 U.S. states, laws restrict or ban automatic substitution of NTI drugs without prescriber approval. In other states, pharmacists can switch generics freely - even for warfarin. A 2019 study found that pharmacists in states with strict NTI laws were 40% less likely to substitute generics for initial prescriptions. Many say they only switch when the patient asks, or when cost is a barrier - and even then, they warn patients to watch for symptoms.

What Should You Do If You’re on an NTI Drug?

If you’re taking an NTI drug, here’s what you need to know:

- Know your drug. Common NTI drugs include warfarin, levothyroxine, lithium, phenytoin, carbamazepine, digoxin, cyclosporine, tacrolimus, and theophylline.

- Ask your pharmacist. When you pick up your prescription, ask: “Is this the same manufacturer as last time?” If it’s not, ask if you can stick with the same one.

- Don’t assume it’s safe. Even if your doctor says generics are interchangeable, monitor yourself. Keep a symptom journal - fatigue, headaches, mood changes, irregular heartbeat, tremors, or seizures could signal a problem.

- Request brand or consistent generic. If you’re stable on a specific brand or generic, ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” or “Do Not Substitute” on the prescription. Most insurers will honor this for NTI drugs if it’s medically justified.

- Get blood tests checked. For drugs like warfarin, lithium, or tacrolimus, regular blood monitoring is essential. Don’t skip tests after a switch - even if you feel fine.

The Bigger Picture

It’s easy to think generics are all the same. But NTI drugs are different. They’re not just cheaper versions - they’re precision tools. A slight variation in absorption can have real consequences. The FDA’s data shows most switches are safe. But real-world evidence shows that for some patients, even a small change can be dangerous.

There’s no perfect solution. Generics save billions in healthcare costs. But for patients on NTI drugs, consistency matters more than cost. If you’ve been stable on one version for months or years, switching for a few dollars less isn’t worth the risk.

Health systems need better tracking - so when you get a new prescription, you know which manufacturer made it. Pharmacists need clearer guidelines. And patients need to be empowered to speak up. You’re not being difficult if you ask to stay on the same generic. You’re being smart.

Final Thought

NTI drugs aren’t like aspirin. You can’t just swap them out and forget about it. They demand attention. If you’re on one, treat it like a high-stakes medication - because it is. Your body isn’t a statistical average. It’s yours. And it deserves consistency.

Are all generic drugs the same, even for NTI medications?

No. While all generics must contain the same active ingredient, the inactive ingredients - like fillers and coatings - can differ between manufacturers. For NTI drugs, these small differences can affect how quickly the drug is absorbed, leading to changes in blood levels. Even if the average bioequivalence meets FDA standards, individual patients may respond differently.

Can I switch between generic manufacturers of levothyroxine safely?

The FDA says yes, and large studies show most patients maintain stable TSH levels after switching. But some individuals do experience changes - especially those with thyroid cancer or severe hypothyroidism. If you’re stable on one brand or generic, it’s safest to stick with it. Always check your TSH level 6-8 weeks after any switch, even if you feel fine.

Why do some doctors refuse to allow generic substitution for antiepileptic drugs?

Although bioequivalence studies show generics are statistically equivalent, real-world reports of breakthrough seizures after switching are common. The American Academy of Neurology advises against automatic substitution because even small fluctuations in blood levels of drugs like phenytoin or carbamazepine can lower the seizure threshold. For patients with epilepsy, maintaining stable drug levels is critical - and consistency reduces risk.

Is warfarin safe to switch between generic versions?

Studies show that switching between generic warfarin manufacturers can increase INR variability - meaning your blood clotting time becomes less predictable. While major bleeding events didn’t rise significantly in one 6-month study, the risk of dangerous INR swings remains. Patients on warfarin should have their INR checked within 1-2 weeks after any switch, regardless of what their doctor says.

What should I do if I think a generic switch caused side effects?

Don’t ignore symptoms. Contact your doctor immediately and mention the recent switch in manufacturers. Ask for a blood test to check drug levels if applicable (like for lithium or tacrolimus). Request to return to your previous version. Keep a record of when you switched and what symptoms appeared - this helps your doctor make the case for a non-substitutable prescription.

Can I ask my pharmacy to always give me the same generic manufacturer?

Yes. You have the right to request the same manufacturer each time. Tell your pharmacist you’re on an NTI drug and want consistency. Many pharmacies can special order a specific generic if they carry multiple brands. If they refuse, ask your doctor to write “Dispense as Written” on the prescription - this legally prevents substitution in most states.

Next Steps

If you’re on an NTI drug and haven’t thought about your generic version in a while, take action now. Check your last prescription - was it the same manufacturer as before? Call your pharmacy and ask. Look up your drug on the FDA’s website to confirm it’s classified as NTI. Talk to your doctor about whether you need to stay on one version. And if you’ve had unexplained symptoms after a switch - don’t brush them off. You’re not imagining it. Your body is telling you something.

sue spark

December 15, 2025 AT 21:26My doctor switched my levothyroxine last month and I felt like a zombie for two weeks. No one warned me. I thought generics were all the same. Turns out they’re not. Now I call the pharmacy before every refill and ask for the exact brand. It’s a pain but worth it.

Tiffany Machelski

December 16, 2025 AT 16:39i just found out my warfarin changed manufacter and i didnt even notice til my inr went crazy. why dont they tell you this stuff? i feel like im playing russian roulette with my meds

SHAMSHEER SHAIKH

December 18, 2025 AT 06:59It is of paramount importance to recognize that the bioequivalence standards established by the FDA, while scientifically rigorous, do not fully account for inter-individual pharmacokinetic variability, particularly in the context of narrow therapeutic index medications. The clinical implications of even marginal fluctuations in serum concentration can be catastrophic, as evidenced by multiple peer-reviewed studies documenting increased rates of organ rejection, seizure recurrence, and thromboembolic events following generic substitution. Therefore, I strongly advocate for the preservation of medication consistency as a non-negotiable element of patient safety.

anthony epps

December 18, 2025 AT 17:47i never knew some pills could be so picky. i thought all generics were just cheaper versions of the same thing. guess not. now i check the name on the bottle every time. better safe than sorry.

Aditya Kumar

December 19, 2025 AT 17:58so basically we’re all lab rats for big pharma and insurance companies. great.

Randolph Rickman

December 19, 2025 AT 23:12Don’t let anyone tell you this isn’t a real issue. I’m a nurse and I’ve seen patients crash after a generic switch. It’s not paranoia - it’s physiology. If you’re on an NTI drug, fight for consistency. Write ‘Do Not Substitute’ on your script. Ask for the same maker every time. You’re not being difficult - you’re being your own best advocate. And if your pharmacist gives you grief? Tell them to call your doctor. We’ve got your back.

James Rayner

December 21, 2025 AT 18:14It’s strange how we treat aspirin like it’s a rock, but a pill that keeps your heart beating or your brain from seizing is treated like a commodity. We optimize our coffee machines, our phones, our cars - but our bodies? We swap out the fuel without asking if it’ll still run. Maybe the real question isn’t whether generics are safe - it’s whether we’ve forgotten how to care for the people who take them.

Josias Ariel Mahlangu

December 21, 2025 AT 23:40People complain about this, but they don’t understand the economics. Generics exist to save money. If you can’t handle a slight variation in your medication, maybe you shouldn’t be on it in the first place. This isn’t a privilege - it’s a responsibility to the system.

Andrew Sychev

December 22, 2025 AT 14:11THEY’RE PLAYING WITH OUR LIVES. ONE DAY YOU’RE FINE, THE NEXT YOU’RE HOSPITALIZED BECAUSE SOMEONE IN CHINA CHANGED A FILLER. NO ONE TELLS YOU. NO ONE CARES. I’M ON TACROLIMUS AND I’VE HAD THREE EMERGENCY ROOM VISITS SINCE THEY SWITCHED MY GENERIC. THIS ISN’T MEDICINE - IT’S A GAME OF RUSSIAN ROULETTE WITH A SIDE OF PROFIT.