Professional Liability and Generic Substitution: Reducing Risk for Pharmacists

Dec, 1 2025

Dec, 1 2025

When a pharmacist swaps a brand-name drug for a generic, they’re not just saving money-they’re stepping into a legal gray zone. In 2025, this decision carries real risk. One wrong move, one missed notification, one unrecorded consent, and a pharmacist could face a malpractice claim-even if the generic is FDA-approved and bioequivalent. The problem isn’t the drugs. It’s the system.

Why Generic Substitution Isn’t as Simple as It Looks

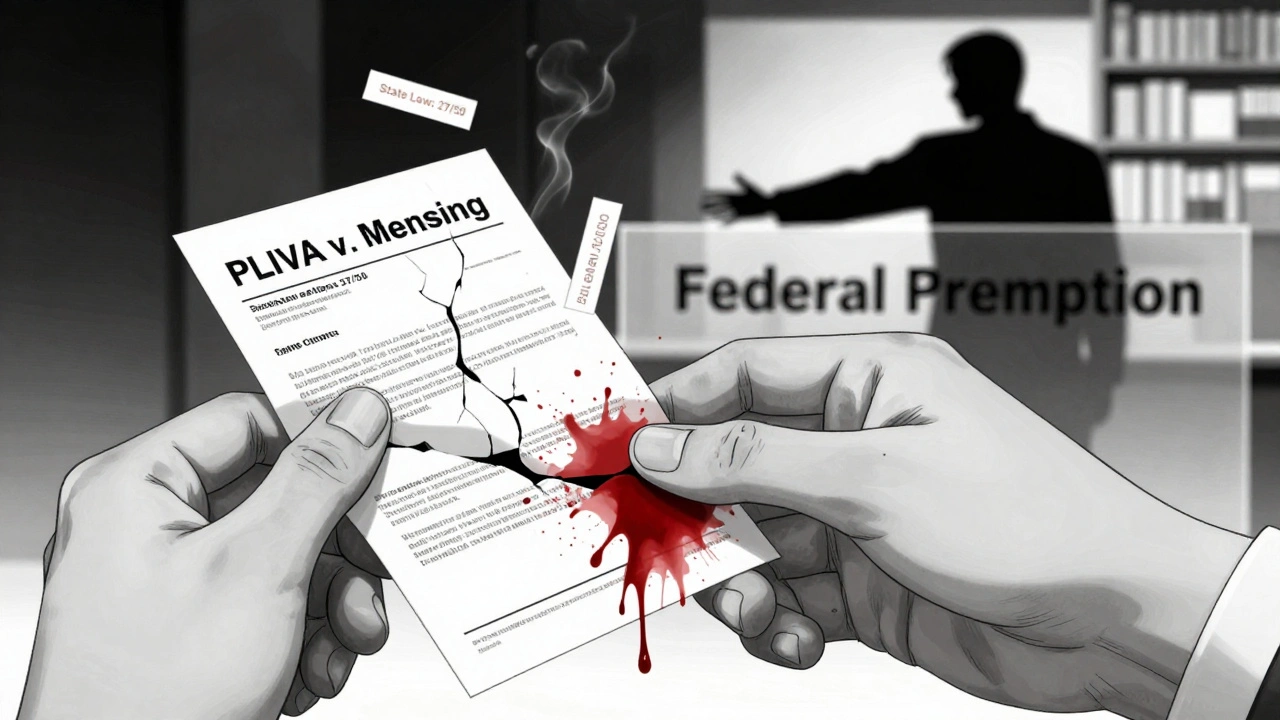

Generic drugs save the U.S. healthcare system over $1.6 trillion every decade. That’s huge. But behind that number is a patchwork of 50 different state laws, federal preemption rules, and silent patient concerns. The 1984 Hatch-Waxman Act made generics possible. The 2011 Supreme Court case PLIVA v. Mensing made it dangerous. That ruling said generic manufacturers can’t be sued for failing to update warning labels. Why? Because federal law forces them to copy the brand-name label exactly. They can’t add a warning about a new side effect, even if they see it in their own data. So if a patient has a bad reaction, there’s no one legally responsible. Not the manufacturer. Not always the doctor. Sometimes, not even the pharmacist. And yet, pharmacists are still expected to make the substitution. In 27 states, they’re required to substitute unless the prescriber says no. In 23 others, they can but don’t have to. That means your liability depends on where you work. In Connecticut, a pharmacist can be held liable for substitution even if the law allows it. In Texas, the law explicitly protects them. It’s a legal roulette wheel.The Real Danger: Narrow Therapeutic Index Drugs

Not all generics are equal. For drugs like warfarin, levothyroxine, and antiepileptics, tiny differences in absorption can be life-changing. These are called narrow therapeutic index (NTI) drugs. The margin between effective and toxic is razor-thin. A 2017 study in Epilepsy & Behavior found that 18.3% of patients had therapeutic failure after switching from brand to generic antiepileptic drugs. That’s nearly one in five. One patient had a seizure. Another developed permanent neurological damage. The court dismissed the case because federal law blocked liability against the generic maker. The pharmacist? They followed state law. No one was held accountable. The American Epilepsy Society says generic substitution for antiepileptics increases seizure risk by 7.9%. That’s not a small number. Yet in many states, pharmacists don’t need to tell patients they’re switching. In 32 states, patients can refuse substitution-but only if they’re told it’s happening. And too often, they’re not. A 2021 Patient Advocacy Foundation survey found that 41% of patients didn’t know their prescription had been switched until they felt worse. One Reddit user shared how switching to generic levothyroxine left them with crushing fatigue, weight gain, and brain fog. Their pharmacist didn’t mention the change. Their doctor didn’t check. It took three months and a blood test to figure out why.What States Are Doing Right (and Wrong)

States with strong liability protections have lower malpractice claims. California, Texas, and Florida require pharmacists to notify patients, get consent for NTI drugs, and document everything. Those states saw 32% fewer substitution-related lawsuits between 2015 and 2019, according to the National Community Pharmacists Association. Compare that to Connecticut and Massachusetts. No mandatory consent. No clear liability shield. Claim rates jumped 27% in the same period. Here’s the breakdown:- 27 states require substitution when appropriate

- 18 states require independent patient notification (beyond the label)

- 32 states let patients refuse substitution

- 27 states protect pharmacists from greater liability for substitution

- 23 states offer no such protection

How Pharmacists Are Reducing Risk Right Now

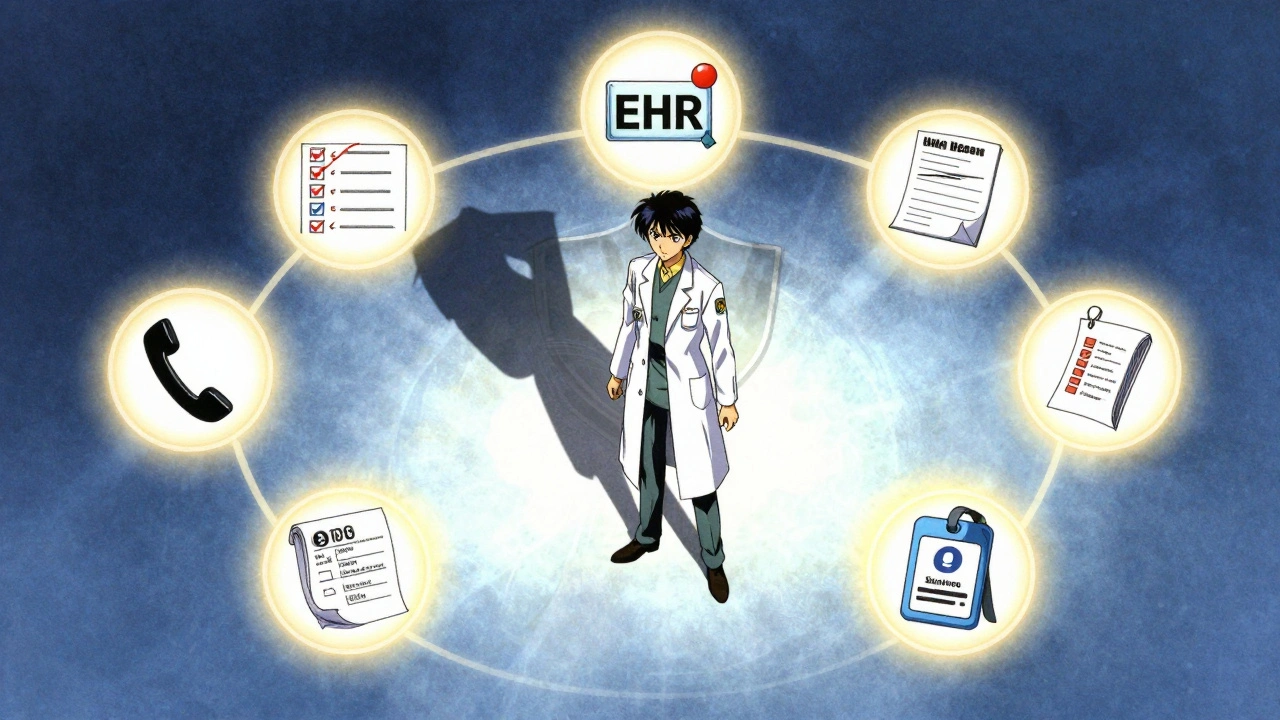

The smart ones aren’t waiting for the law to catch up. They’re building their own safety nets. The American Society of Health-System Pharmacists recommends a seven-step protocol:- Know your state’s rules. Laws change. Check the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy’s annual compendium. Don’t guess.

- Use EHR alerts. Program your system to flag NTI drugs: levothyroxine, warfarin, phenytoin, carbamazepine, cyclosporine, digoxin, lithium. If it’s flagged, pause and verify.

- Get written consent. Use a simple form: “I understand this generic may be different from my previous brand. I agree to this substitution.” Sign it. Date it. File it.

- Call the prescriber. If you’re unsure, ask. A quick call can prevent a crisis. Most doctors appreciate the heads-up.

- Log everything. Record the generic manufacturer, lot number, and date. If something goes wrong, you need to trace it.

- Do a yearly risk audit. Use the 27-point checklist from the Journal of the American Pharmacists Association. It’s not optional anymore.

- Get extra insurance. Standard malpractice policies often exclude substitution-related claims. Buy supplemental coverage. It costs $300-$800 a year. Worth it.

The Patient’s Side: Why They’re Angry-and Confused

Patients aren’t the enemy. They’re the ones caught in the middle. GoodRx users love generics for cost savings. On average, they save $327.50 a year on meds like lisinopril and metformin. Eighty-two percent are happy. But for NTI drugs? The story flips. A 2022 survey of 2,345 patients found that 28% said their pharmacist never gave them the legally required notice. One woman in Pennsylvania switched to a generic warfarin. Her INR dropped. She had a stroke. She didn’t know the generic was different. She didn’t know she had the right to refuse. A 2022 Johns Hopkins survey found that 63% of patients couldn’t name their state’s substitution laws. They assume all generics are the same. They assume the pharmacist is looking out for them. When things go wrong, they blame the pharmacist. And they’re not wrong to. Because even if the law says you’re protected, the patient doesn’t care. They just want someone to answer for what happened.

What’s Changing? The Future of Liability

The system is cracking. In 2023, 11 states introduced the Generic Drug Safety Act. It would force brand-name manufacturers to update labels within 30 days of new safety data-and require generics to adopt those updates within 60 days. That’s a huge shift. It could finally close the liability gap. The FDA’s 2023 pilot program for labeling changes has approved 68% of requests. But here’s the catch: only 12% came from generic manufacturers. They’re still afraid to act. Meanwhile, biosimilars are coming. Fourty-five states now allow substitution of biologic drugs like Humira and Enbrel. But liability rules for these are even less clear. The same legal mess is about to get bigger. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the current system costs $4.2 billion a year in unaddressed adverse events. The Institute for Clinical and Economic Review says fixing it could raise generic prices by 7-12%-but prevent 14,000 serious injuries annually. Is that worth it? For patients, yes. For pharmacists? Absolutely.Your Action Plan for 2025

You can’t wait for Congress or your state legislature to fix this. Here’s what to do now:- Stop assuming. Just because a drug is generic doesn’t mean it’s interchangeable-especially for NTI drugs.

- Always notify. Even if your state doesn’t require it, tell the patient. Say it out loud. Write it down.

- Document everything. Your paper trail is your shield.

- Know your NTI drugs. Memorize the list. Set alerts. Don’t rely on memory.

- Get supplemental insurance. It’s not expensive. It’s essential.

- Speak up. Talk to your state pharmacy board. Push for consent laws. Join the conversation.

Can a pharmacist be sued for substituting a generic drug?

Yes, but it depends on the state and the drug. In 27 states, pharmacists are protected from greater liability for substitution than if the brand-name drug were dispensed. In 23 states, there’s no such protection. For narrow therapeutic index drugs like warfarin or levothyroxine, liability risk increases significantly-even in protected states-if proper consent and documentation aren’t followed. Federal law blocks lawsuits against generic manufacturers, so patients often target pharmacists instead.

Do I need patient consent to substitute a generic drug?

It depends on your state. Thirty-two states allow patients to refuse substitution, but only 18 require you to notify them independently (not just via the label). Best practice? Always get written consent for any substitution, especially for narrow therapeutic index drugs. Even if your state doesn’t require it, having a signed form protects you legally and ethically.

Are all generic drugs safe to substitute?

No. Generic drugs must be bioequivalent (80-125% absorption range) to the brand-name version, but that doesn’t guarantee therapeutic equivalence. For drugs with a narrow therapeutic index-like antiepileptics, warfarin, levothyroxine, and lithium-small differences in absorption can cause serious harm. Studies show up to 18.3% of patients experience therapeutic failure after switching these drugs. Always verify the drug class before substituting.

What should I do if a patient has a bad reaction after a generic substitution?

First, assess the patient’s condition and provide care. Then, document everything: the drug name, manufacturer, lot number, date of substitution, and any patient communication. Review your state’s substitution laws to determine if you followed protocol. Contact your malpractice insurer immediately. If you didn’t get consent or document the change, you may be at risk-even if the substitution was legally allowed.

How can I reduce my liability risk as a pharmacist?

Use a seven-step protocol: (1) Know your state’s substitution laws, (2) Use EHR alerts for narrow therapeutic index drugs, (3) Get written patient consent, (4) Communicate with prescribers when in doubt, (5) Log all substitutions with batch numbers, (6) Complete an annual liability risk assessment, and (7) Obtain supplemental malpractice insurance that covers substitution-related claims. These steps cut your risk by over 70% according to pharmacy risk management studies.

Why can’t generic manufacturers update their drug labels?

Because of federal preemption. The Supreme Court ruled in PLIVA v. Mensing (2011) that generic manufacturers must use the same label as the brand-name drug and cannot unilaterally change it. Even if they discover new safety risks, they’re legally barred from updating the label unless the brand-name manufacturer does first. This creates a liability gap where patients are injured but no one can be held accountable under state law.

Joel Deang

December 2, 2025 AT 15:10bro i just switched my thyroid med to generic and felt like a zombie for 3 months 😅 no one told me. now i know why my cat stares at me like i’m possessed.

Arun kumar

December 4, 2025 AT 13:28the real tragedy is not the law but the silence. we treat medicine like a commodity but forget it’s a human experience. if a pill changes your mind, shouldn’t you know which one you’re taking?

Zed theMartian

December 6, 2025 AT 12:22oh please. you’re all acting like pharmacists are saints. they’re just corporate drones following scripts written by lawyers who’ve never held a stethoscope. if you want safety, stop outsourcing your brain to an algorithm that says ‘substitute’ and start asking questions. or better yet-don’t take the damn pills.

Shannara Jenkins

December 8, 2025 AT 06:00Thank you for writing this. As a pharmacist, I’ve been terrified to substitute levothyroxine for years. I always call the prescriber and get written consent-even in states where it’s not required. It’s not about fear, it’s about care. And yes, I bought supplemental insurance. Worth every penny.

Roger Leiton

December 8, 2025 AT 19:19🔥 just had a patient ask me why her seizures came back after switching generics. I pulled up the 2017 Epilepsy & Behavior study and showed her. She cried. Then she thanked me. That’s why I do this. Not for the money. For the moments like that.

Laura Baur

December 9, 2025 AT 08:02It is profoundly disconcerting that a profession entrusted with the administration of life-altering pharmaceuticals operates under a regulatory patchwork so chaotic it borders on criminal negligence. The absence of federal standardization is not merely an administrative lapse-it is a moral failure of epic proportions. The FDA’s passive stance, coupled with judicial abdication via PLIVA v. Mensing, has effectively created a liability vacuum wherein the most vulnerable bear the burden of systemic indifference. This is not healthcare. This is pharmaceutical roulette with a loaded chamber.

Jack Dao

December 11, 2025 AT 02:15you guys are overreacting. if you can’t handle a little liability, maybe you shouldn’t be a pharmacist. everyone knows generics are cheaper. if the patient doesn’t like it, they can pay more. problem solved.

dave nevogt

December 12, 2025 AT 16:19I’ve worked in community pharmacy for 22 years. I’ve seen patients switch to generics and feel fine. I’ve also seen them crash. The difference isn’t always the drug-it’s the silence between the prescription and the patient. The real issue isn’t the law. It’s that we stopped talking. We stopped listening. We started thinking our job was to fill bottles, not save lives. Maybe we need to remember why we got into this.

Steve World Shopping

December 14, 2025 AT 14:43The structural asymmetry in pharmaceutical liability regimes manifests as a pathological misalignment between regulatory compliance and clinical accountability. The absence of manufacturer-level label autonomy constitutes a systemic failure of pharmacovigilance infrastructure, thereby externalizing risk to frontline providers who lack the requisite legal shield. This constitutes a textbook case of institutionalized moral hazard.

Rebecca M.

December 14, 2025 AT 15:58soooo… you’re telling me the guy who handed me my insulin generic didn’t tell me it was different… and now I’m in the hospital? lol. guess I’ll just sue the pharmacist who ‘followed the rules’ while the real culprits hide behind federal law. classic.

Elizabeth Grace

December 15, 2025 AT 08:18i just found out my anxiety meds were switched and i’ve been crying for 2 weeks straight. i didn’t know i could say no. why does no one ever tell you these things? i feel so stupid for trusting everyone.

Steve Enck

December 16, 2025 AT 05:47It is an incontrovertible fact that the current regulatory architecture incentivizes cost minimization over patient safety, thereby creating a perverse moral economy wherein the most vulnerable are systematically exploited under the guise of fiscal responsibility. The legal immunity granted to generic manufacturers, coupled with the inconsistent state-level protections afforded to pharmacists, constitutes a structural violation of the duty of care. The only ethical response is the immediate imposition of federal liability standards, mandatory patient notification protocols, and universal supplemental malpractice coverage-otherwise, we are complicit in a system that commodifies human physiology.

मनोज कुमार

December 17, 2025 AT 18:10generic = cheap. patient = dumb. pharmacist = scapegoat. law = broken. fix it or shut up.