Type A vs Type B Adverse Drug Reactions: What You Need to Know

Dec, 17 2025

Dec, 17 2025

Adverse Drug Reaction Type Calculator

Type A vs Type B Reaction Assessment

This tool helps you determine if your medication reaction is more likely Type A (predictable) or Type B (unpredictable) based on the article's classification system.

Reaction Details

When you take a medication, you expect it to help-not hurt. But sometimes, even the right drug at the right dose can cause unexpected problems. Not all side effects are the same. Some are common and predictable. Others are rare, scary, and come out of nowhere. That’s where the Type A vs Type B classification system comes in. It’s not just medical jargon-it’s a practical tool doctors and pharmacists use every day to spot danger before it happens.

What Are Type A Adverse Drug Reactions?

Type A reactions are the most common. In fact, 85 to 90% of all adverse drug reactions fall into this category. They’re predictable. They happen because of how the drug works in your body-not because of some hidden flaw in you.

Think of them as an extension of the drug’s normal effect, just turned up too high. For example, if you take a blood pressure pill and your blood pressure drops too far, causing dizziness or fainting, that’s a Type A reaction. Same with stomach upset from NSAIDs like ibuprofen. It’s not random-it’s a direct result of the drug’s pharmacology.

These reactions are dose-dependent. The higher the dose, the more likely and severe they become. That’s why overdoses are almost always Type A. Take too much acetaminophen? Liver damage follows. Take too much insulin? Blood sugar crashes. There’s a clear line between therapeutic effect and toxicity.

Common examples include:

- Hypotension from antihypertensives (affects 10-20% of patients)

- Gastrointestinal bleeding from long-term NSAID use

- Sedation from benzodiazepines

- Low potassium from diuretics

- Constipation from opioids

The good news? Type A reactions are usually preventable. Your doctor can adjust your dose, switch you to a different drug, or monitor you more closely. If you’ve had a reaction before, telling your provider can help avoid it next time.

What Makes Type B Reactions So Dangerous?

Type B reactions are the opposite. They’re rare-only 5 to 10% of all adverse reactions-but they’re responsible for about 30% of hospitalizations due to drug problems. Why? Because they’re unpredictable. They have nothing to do with the drug’s intended action. They’re not dose-related. And they can strike anyone, even at the lowest dose.

These are the reactions that scare doctors. They’re often immune-driven. Your body sees the drug-or a piece of it-as an invader and attacks. Or your liver breaks it down in a weird way that creates a toxic byproduct. Sometimes, it’s genetics. You might carry a gene that makes you extra sensitive, but there’s no test for it until after the reaction happens.

Classic examples:

- Stevens-Johnson syndrome from sulfonamides (1-6 cases per million prescriptions)

- Anaphylaxis from penicillin (0.01-0.05% of courses)

- Malignant hyperthermia from anesthesia (1 in 15,000 to 50,000 exposures)

- Drug-induced lupus from hydralazine or procainamide

These reactions can be fatal. A rash from amoxicillin might seem harmless, but if it turns into toxic epidermal necrolysis, it’s a medical emergency. There’s no safe way to test for these reactions before they happen. The only reliable prevention? Avoiding the drug entirely if you’ve had one before.

Why the A/B System Isn’t Enough Anymore

The Type A and Type B system was created in the 1970s, and it’s still useful. But medicine has moved on. We now know that some reactions don’t fit neatly into those two boxes.

That’s why experts use an expanded six-type system (A-F):

- Type C: Chronic effects from long-term use. Like adrenal suppression from taking prednisone for more than three weeks.

- Type D: Delayed reactions that show up months or years later. The most infamous example? Diethylstilbestrol causing clear cell adenocarcinoma in daughters of women who took it during pregnancy.

- Type E: Withdrawal reactions. Opioid withdrawal in 80-90% of dependent patients within 12-30 hours of stopping. Or rebound hypertension after suddenly stopping clonidine.

- Type F: Therapeutic failure. When a drug stops working because of another drug. Like birth control pills failing when taken with rifampin.

These categories help explain reactions that don’t fit Type A or B. A reaction that builds slowly over months? Type C. A reaction that hits years later? Type D. These aren’t just academic distinctions-they change how you monitor patients and when you look for trouble.

How Doctors Actually Use This in Real Life

Most doctors don’t walk around thinking, “Is this Type A or Type B?” But they think about the same things without using the labels.

When a patient says, “I feel dizzy after taking my blood pressure pill,” the doctor thinks: “Is this because the dose is too high? Or is this something new?” If the patient just started the drug, and the dose was recently increased, it’s likely Type A. Adjust the dose. Wait a few days. See if it improves.

But if the patient took the same dose for months without issue, then suddenly broke out in a full-body rash? That’s a red flag for Type B. Stop the drug. Refer to a specialist. Don’t try to “tough it out.”

Surveys show that 78% of physicians find the A/B system moderately useful-but they rely on experience and context more than labels. One doctor told a Reddit thread: “I don’t care if it’s Type A or B. I care if it’s going to kill them.”

Pharmacists, though, use the full six-type system more often. They’re the ones reviewing drug interactions, tracking long-term use, and flagging withdrawal risks. In European pharmacovigilance centers, 92% use the expanded system. In the U.S., 78% of serious ADR reports submitted to the FDA in 2022 used it too.

What About Genetics and Personalized Medicine?

Here’s the big shift: many Type B reactions are starting to look less “idiosyncratic” and more like genetic risks.

Take carbamazepine. In some people, it causes a severe skin reaction called SJS. Turns out, if you carry the HLA-B*15:02 gene-common in people of Southeast Asian descent-you’re at much higher risk. Testing for that gene before prescribing can prevent the reaction entirely.

Same with abacavir (an HIV drug). The HLA-B*57:01 gene test is now standard before starting treatment. If you have it, you don’t get the drug. No more guessing.

Experts like Dr. Robert S. Hoffman say we’re seeing a “paradigm shift.” What we used to call Type B is now often Type A… but with a genetic twist. The reaction is still rare, but now we can predict who’s at risk.

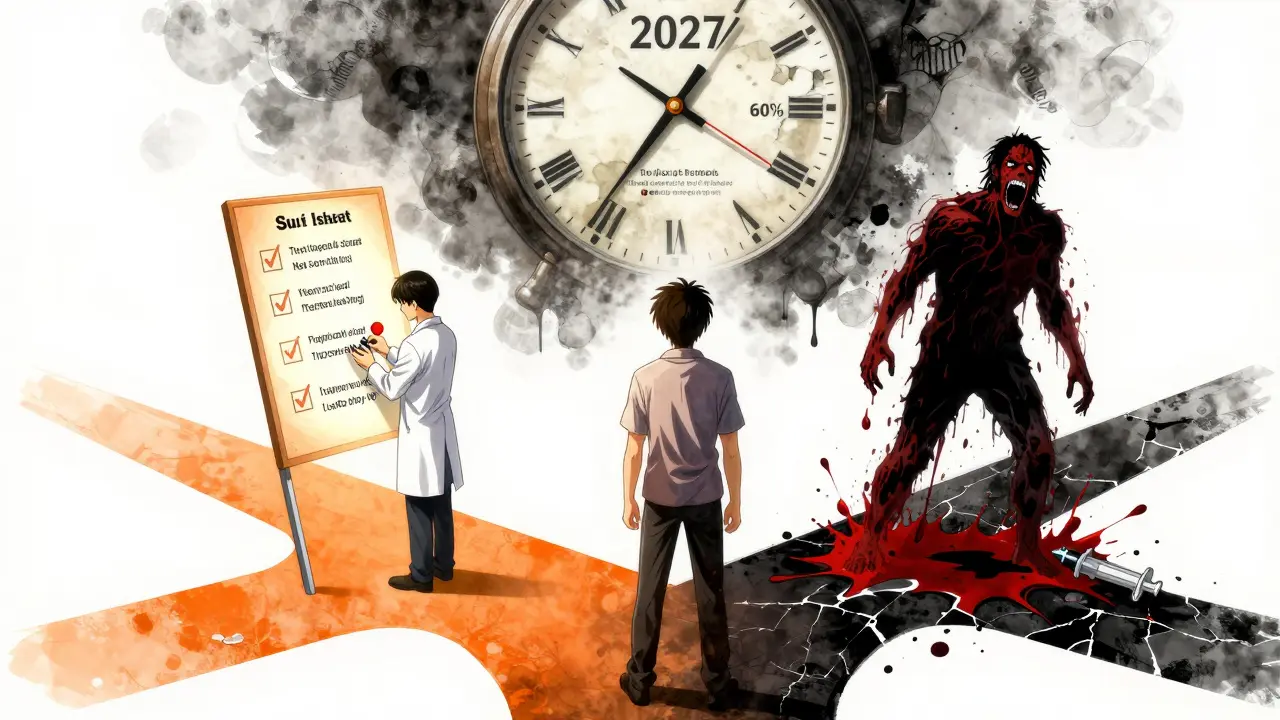

By 2027, McKinsey predicts that 60% of what we now call Type B reactions will have identifiable genetic markers. That means fewer surprises. Fewer deaths. More targeted prescribing.

What You Should Do as a Patient

You don’t need to memorize the classification system. But you should know how to protect yourself.

- Keep a list of all medications you’ve taken and any reactions you’ve had-even if you think it was minor.

- Tell your doctor about every side effect, even if it seems unrelated. A rash after a new antibiotic? Say it. Dizziness after a new statin? Say it.

- Ask: “Could this be a common side effect, or something rare?”

- If you’ve had a serious reaction before, get it documented in your medical record. Ask for an allergy bracelet if needed.

- Don’t assume a reaction won’t happen again just because it was mild last time. Type B reactions can get worse with each exposure.

And if you’re on a drug that’s known to cause serious reactions-like carbamazepine, allopurinol, or abacavir-ask if genetic testing is available. It’s not always offered, but it’s becoming standard for high-risk drugs.

Why This Matters for Your Safety

Drug reactions kill more people than car accidents in the U.S. every year. And most of those deaths come from reactions that could have been avoided.

Type A reactions? We can prevent them with better dosing, monitoring, and communication. Type B? We can’t prevent them all-but we can prevent more of them with genetic testing, better reporting, and awareness.

The bottom line: not all side effects are created equal. Some are annoying. Some are dangerous. Some are life-threatening. Understanding the difference isn’t just for doctors. It’s for anyone who takes medication.

Next time you get a new prescription, ask: “What are the most common side effects? And what’s the worst thing that could happen?” That’s not being paranoid. That’s being smart.

What’s the difference between Type A and Type B adverse drug reactions?

Type A reactions are predictable, dose-dependent, and related to the drug’s normal pharmacology-like dizziness from blood pressure meds or stomach upset from NSAIDs. They make up 85-90% of all adverse reactions. Type B reactions are unpredictable, not dose-related, and often immune-mediated-like severe rashes or anaphylaxis. They’re rare (5-10%) but cause most serious, life-threatening reactions.

Are Type B reactions always allergic?

No. While many Type B reactions are immune-mediated (like anaphylaxis or Stevens-Johnson syndrome), others are idiosyncratic metabolic reactions-meaning your body processes the drug in an unusual way that creates a toxic substance. These aren’t allergies; they’re genetic or enzymatic quirks. For example, malignant hyperthermia from anesthesia isn’t an allergic response-it’s a muscle cell malfunction triggered by the drug.

Can Type A reactions be serious?

Yes. While Type A reactions are common and usually mild, they can be deadly if not caught. Acetaminophen overdose causes thousands of liver failures each year. Too much warfarin leads to fatal bleeding. Even common drugs like diuretics can cause dangerous electrolyte imbalances. The key is that they’re preventable with proper dosing and monitoring.

Why do some drugs cause reactions in only some people?

It’s often genetics. Your liver enzymes, immune system, and drug transporters vary from person to person. Some people have genes that make them slow metabolizers, leading to drug buildup. Others have immune markers that trigger severe reactions. That’s why testing for HLA-B*15:02 before prescribing carbamazepine is now standard-it prevents deadly skin reactions in high-risk populations.

Is there a way to predict Type B reactions before taking a drug?

For some, yes. Genetic tests exist for drugs like abacavir, carbamazepine, and allopurinol. If you test positive for the risk gene, you avoid the drug. But for most Type B reactions, there’s still no test. That’s why reporting any unusual reaction to your doctor or through systems like MedWatch is so important-it helps identify new patterns.

What’s the six-type classification system, and why does it matter?

It expands the basic A/B system to include chronic effects (Type C), delayed reactions (Type D), withdrawal symptoms (Type E), and therapeutic failures (Type F). This matters because it helps doctors catch problems that don’t fit the original two categories. For example, adrenal suppression from long-term steroids is Type C-not Type A, even though it’s dose-related. The six-type system gives a fuller picture for safety monitoring and reporting.

What Comes Next for Drug Safety?

The future of drug safety isn’t just about better labels or more warnings. It’s about prediction. The FDA and WHO are already integrating pharmacogenomics into ADR reporting. By 2025, the ICH will require the six-type classification as the global standard for serious adverse events.

AI tools are being trained to spot patterns in millions of ADR reports-flagging clusters of reactions that might point to new risks. Hospitals are building automated alerts into electronic records to warn doctors when a patient has a history of a Type B reaction.

But the foundation hasn’t changed. Type A and Type B still separate the predictable from the unpredictable. And until we can test for every possible genetic risk, that distinction remains one of the most important tools in medicine.

Mike Rengifo

December 18, 2025 AT 11:00Been on blood pressure meds for 5 years. Type A? Yeah, I get dizzy if I stand up too fast. Doc lowered my dose and now I’m fine. No big deal. Just don’t skip your checkups.

Ashley Bliss

December 19, 2025 AT 13:55People treat drugs like candy. ‘Oh, I’ll just take an extra pill if I’m in pain.’ Then they wonder why their liver’s failing. This isn’t a game. It’s your body screaming for help-and you’re ignoring it because you’re too lazy to read the label. Wake up. You’re not special. Your body doesn’t care about your ‘I know what I’m doing’ attitude. Type A reactions? They’re not accidents. They’re consequences.

Dev Sawner

December 20, 2025 AT 19:04While the Type A and Type B classification system remains a foundational paradigm in pharmacovigilance, its utility is increasingly constrained by the absence of granular genetic and metabolic profiling in clinical practice. The proposed expansion to a six-type taxonomy (A-F) constitutes a necessary evolution, particularly in resource-limited settings where pharmacogenomic screening is not routinely accessible. However, the absence of standardized implementation protocols across regulatory jurisdictions undermines its global efficacy. Furthermore, the assertion that 60% of Type B reactions will be genetically predictable by 2027 is statistically optimistic without longitudinal cohort validation. The reliance on HLA-B*15:02 screening for carbamazepine is commendable, yet it remains an exception rather than a rule. Systemic integration of pharmacogenomics into primary care remains a distant aspiration, not a current reality.

Meenakshi Jaiswal

December 22, 2025 AT 05:33Hey, if you’re on abacavir or carbamazepine-ask your doctor about genetic testing. Seriously. It’s a simple blood test. In India, some hospitals now offer it for free under public health programs. I’ve seen patients avoid life-threatening rashes just because someone asked the right question. Don’t wait until you’re in the ER. A quick check could save your skin-literally. And if your doc says ‘we don’t do that here,’ ask for a referral. You deserve to be safe.

bhushan telavane

December 23, 2025 AT 04:33Bro, in India we just take whatever the pharma rep gives us. No one talks about Type A or B. But I’ve seen my uncle get a rash from amoxicillin and just stop taking it. No doctor. No test. Just ‘nah, not again.’ Maybe the system’s dumb, but people still figure it out. Keep it simple.

Mahammad Muradov

December 24, 2025 AT 01:50It is a fallacy to suggest that Type B reactions are ‘unpredictable.’ The term is merely an admission of clinical ignorance. The absence of diagnostic tools does not equate to the absence of causality. The HLA-B*57:01 association with abacavir hypersensitivity was identified in 2002. The fact that this test is not universally mandated reflects institutional negligence, not biological randomness. To label such reactions as ‘idiosyncratic’ is to absolve the medical establishment of its duty to implement known science. This is not medicine-it is negligence dressed in jargon.

Connie Zehner

December 24, 2025 AT 14:35OMG I had a Type B reaction once 😭 I took a Z-pack and broke out in this FULL BODY RASH and felt like I was dying!! I cried for 3 hours and my mom called 911 and now I’m terrified of EVERY MEDICINE 😭😭😭 I just want to live but I’m scared to take anything!! 😭 Is there a support group?? I need to talk to someone who gets it!! 🥺🥺

holly Sinclair

December 24, 2025 AT 23:59What’s fascinating here isn’t just the classification-it’s the underlying epistemological shift. We’ve moved from viewing drug reactions as either ‘normal’ or ‘random’ to recognizing them as expressions of individual biological variance. Type A was always about dosage and pharmacokinetics, but Type B? It’s a mirror held up to our genetic diversity. The real tragedy isn’t the reactions themselves-it’s that we spent decades calling them ‘idiosyncratic’ while ignoring the fact that they were screaming for a personalized approach. The six-type system isn’t just a taxonomy-it’s a philosophical reckoning. We thought medicine was about universal rules, but it’s always been about individual thresholds. The HLA tests? They’re not just diagnostics-they’re the first real steps toward honoring the uniqueness of each body. And if we’re honest, that’s the most radical thing medicine has done in decades. We’re not just treating disease anymore. We’re learning how to listen to the body’s language, one gene at a time.